A Year with no Easter?

Most of the converts to the new faith were Jews by birth, culture, and religion. All the original Apostles were Jews. Even after the influx of Gentile converts, leadership of the church was overwhelmingly Jewish.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the calendar of the early church was the Jewish calendar. The seven-day week, which had not yet become dominant in the Roman world at large, provided the rhythm of religious life. (It was not until the 4th century, during the reign of Constantine, that the seven-day week was formally established in the Roman calendar.)

In the Jewish calendar, the first six days of the week were not named. Each day was designated by its number in relation to the Sabbath, except for when the sixth day was referred to as the “preparation day.” There were no Sundays or Mondays or Tuesdays, etc.

Our familiar ecclesiastical calendar did not exist back in the 1st Christian century. There was no Easter, no Lent, no Halloween, no Christmas. The annual holy days were the ones in the Jewish calendar: Passover, Pentecost, etc. Sabbath, the seventh day of the Jewish week, was the regular day of worship for both Jews and Christians.

There is no biblical or historical evidence of a “Sunday” Sabbath in that era.

New Testament manuscripts never mention Easter, but the translators of the King James Version used the word in Acts 12:4 for the Greek word, “pascha.” “Pascha” means “Passover.”

When Christians began to commemorate what we call “Easter” they were not focused on Christ’s resurrection. Instead, they observed the anniversary of His death – at Passover. Passover was the fourteenth day of Nisan, the first month of the Jewish religious calendar. It could fall on any day of the week.

During the first half of the 2nd century a strong anti-Sabbath movement developed within the church, particularly among Gentile Christians. This movement went hand in hand with a deepening anti-Jewish sentiment. Influential church leaders in Rome and Alexandria promoted Sunday as the new weekly day of worship. Annual celebration of the resurrection of Christ, fixed to the first day of the week, became more and more popular.

During the 2nd and 3rd centuries Christians were divided over the Passover/Easter schedule. Many church fathers, particularly in Asia Minor, persisted in the Passover observance on Nisan 14, regardless of which day of the week it fell on. They earned the nickname, “fourteeners” – “quartodecimans.” Others, particularly in Rome, wanted to cut the celebration free from the Jewish calendar.

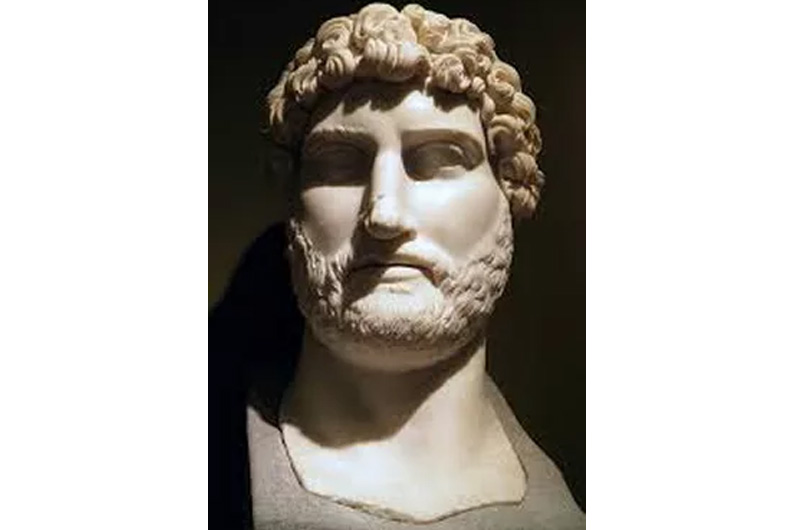

The issue was officially settled at the Council of Nicaea (325 AD). Constantine, the emperor, revealed the strong anti-Jewish motivation behind the council’s decision: “It appears an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews…. Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd.” (Eusebius, “Life of Constantine”)