One Day Above Another?

Was the Apostle Paul taking a stand against Sabbath observance when he wrote Romans 14:5? This verse is commonly used in anti-Sabbath arguments today. Let’s take a look.

“One person considers one day more sacred than another; another considers every day alike. Each of them should be fully convinced in their own mind” (Romans 14:5 NIV).

Check out the context. Notice how Paul introduces this section of his letter: “Accept the one whose faith is weak, without quarreling over DISPUTABLE MATTERS” (Romans 14:1 NIV).

Paul may have been addressing an actual situation within some Christian congregations. Church members were arguing over DISPUTABLE MATTERS. They were criticizing each other over matters of personal opinion. He mentions two issues: diet and holy days.

He doesn’t take sides. He simply points out that “Whoever regards one day as special does so to the Lord. Whoever eats meat does so to the Lord, for they give thanks to God; and whoever abstains does so to the Lord and gives thanks to God” (Romans 14:6 NIV).

So, what were those DAYS Paul referred to? The cultural and historical background suggests that they could have been annual Jewish holy days or days designated for fasting. It’s only natural that a Jewish convert to Christianity—having a tender conscience—would continue to honor those holy days. According to Paul, there is nothing wrong with that as long as it is characterized by sincere worship of the Lord.

What is clear is that Paul was not addressing weekly Sabbath observance. He was talking about DISPUTABLE MATTERS. There is no biblical or historical evidence that the Sabbath was a DISPUTABLE MATTER in Paul’s day.

DISPUTABLE MATTERS would include things that have not been addressed by divine revelation through angels, prophets, or apostles. These are things that people can decide for themselves—matters of personal preference or conviction.

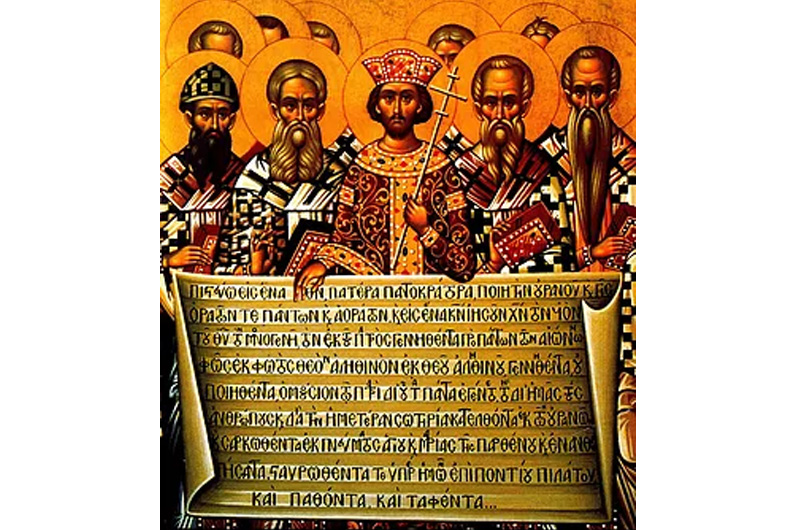

This automatically eliminates from consideration all points of doctrine that are INDISPUTABLE – because they are based on divine injunction or on other authoritative teachings from the Word of God. So, observance of the Sabbath cannot be at issue in Romans 14. After all, the law of the Sabbath was written by the hand of God in the very heart of the Ten Commandments.

The Wesleyan Bible Commentary puts it this way: “Of course this whole discussion concerns matters on which God has not spoken clearly in His word. No such questions can be conscientiously raised concerning the fundamental moral issues that are clarified in the Decalogue, the Sermon on the Mount, or in any other plain statement of Scripture. When God has spoken there is no other legitimate side to the issue.”*

*Wilber T. Dayton, Romans and Galatians, Wesleyan Bible Commentary Vol. 5 (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1965), 86.